In this briefing from the RCEM Policy Team, we explore what NHS England set out to achieve with the UEC Recovery 10 Point Action Plan, and how well it has fared.

Introduction

As the NHS emerges from one of the most difficult periods in its 73-year history, it continues to face unrelenting challenges. Even before the pandemic, there were unprecedented levels of demand placed on Emergency Departments (EDs), which were not met with sufficient investment into the NHS. Despite the publication of the Urgent and Emergency Care (UEC) Recovery 10 Point Action Plan in September 2021, the NHS experienced a record-breaking year for poor performance across the UEC pathway. This briefing will assess the impact of the 10 Point Plan on the UEC pathway and outline key areas of focus for NHS England’s forthcoming UEC strategy, due to be published Autumn 2022.

Policy context

Winter 2020/21 coincided with the second wave of coronavirus in England. Staff related absences due to coronavirus, seasonal pressures, and Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures placed a significant burden on the whole UEC system. Our Retain, Recruit, Recover report (2021) examined the impact of the pandemic on our membership. Alarmingly it found that 59% of respondents described their levels of stress and exhaustion as higher than normal.[1] In Spring 2021, RCEM’s Summer to Recover campaign urged policymakers to use the summer months effectively to prepare for the significant challenges ahead.[2]

In August 2021, we published an explainer examining What’s behind the increase in demand in Emergency Departments?[3]This noted that numbers of ED attendances and subsequent admissions were not only reaching pre-pandemic levels but surpassing them. In June 2021, attendances to Type 1 EDs were the highest on record whilst admissions were the second highest since the start of the pandemic. At this point, EDs were experiencing winter pressures in the summer months.

We warned that if action was not taken to manage demand and improve capacity in EDs ahead of winter 2021/22 then the NHS would find it extremely challenging to provide safe and timely emergency care to its patients. It was against this backdrop that the 10 Point Plan was published. It detailed how the whole system would work together to recover urgent and emergency services, focusing on immediate and medium-term activities. The plan aimed to “to mitigate against the current pressures felt across systems and improve performance in all settings”. At the time of publishing, we emphasised the plan was a good starting point but cautioned that we must see the ambitions of the plan translated into effective action.[4]

It is important to note that the 10-Point Plan did not articulate an overarching, long term, strategic vision for the UEC system. In fact, such a document does not exist. Without this, there is no clarity on what NHS England planned to achieve through the 10 Point Plan. Additionally, it lacked targets, timelines, and any indication of how progress will be reported against the plan. Crucially, it was not backed up with additional resource.

POINT 1: Supporting 999 and 111 services

In order to tackle operational pressures, the 10-Point Plan promised greater support for 999 and 111 services. This would ensure that, amongst other things, there would be sufficient call-handling capacity at NHS 111, and that cross-system work would facilitate speedier ambulance handovers at Emergency Departments.

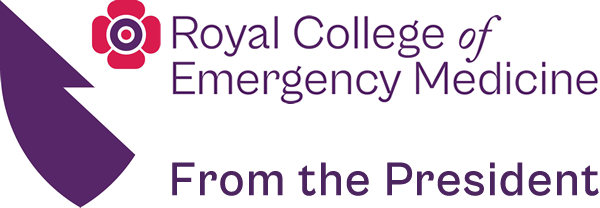

In terms of the former, there does seem to have been a certain amount of success – the time taken to answer calls was lower in the first three months of this year than the preceding three months. Additionally, the proportion of calls abandoned also fell. The ambition to improve NHS 111 capacity seems to have achieved at least one of its principal aims.

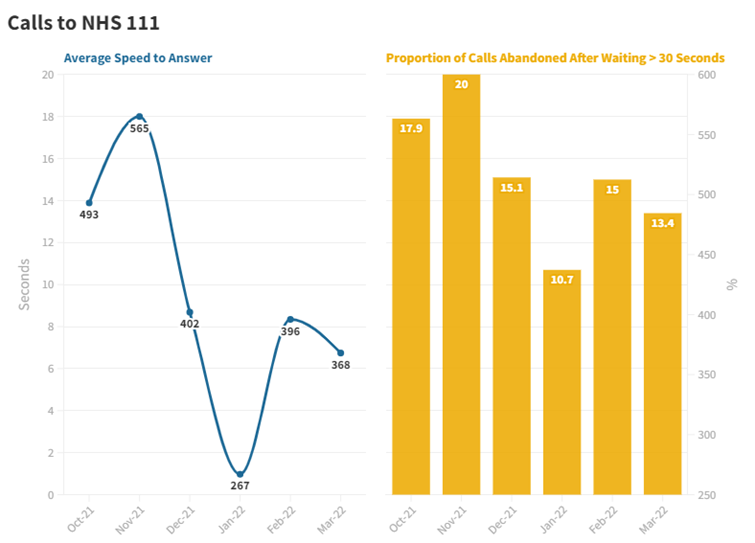

The same was not true of the objective to reduce ambulance handover delays however. There was a substantial increase in the proportion of ambulance offloads involving a delay, even as the number of ambulance arrivals at EDs fell compared with previous years. By week 13 of the 2021/22 Winter SitReps, delays as a proportion of arrivals were 2.7 times higher than the winter of 2020/21.

POINT 3: Supporting greater use of Urgent Treatment Centres (Type 3 and 4 services)

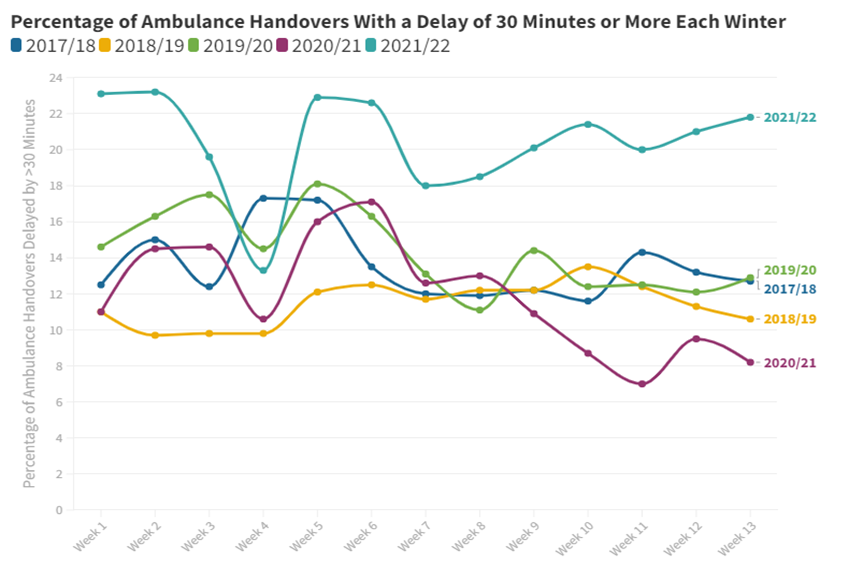

To mitigate against current pressures and improve performance, NHS England outlined the need to utilise Urgent Treatment Centres, specifically Type 3 and 4 services. The graph below displays monthly attendance data for Type 3 services over the past few winters. Attendances to type 3 services were high pre-pandemic. Unsurprisingly, they plummeted in Winter 2020/21 which coincided with the second wave. For Winter 2021/22, the proportion of attendances increased by 4.6 percentage points in comparison to the winter before. However, this pattern of attendances still falls short of pre-pandemic figures.

From December 2017 to March 2018, a monthly average of 98.98% of Type 3 ED patients were admitted, transferred, or discharged within 4 hours. From 2021 to March 2022, a monthly average of 89.11% of Type 3 ED patients were admitted, transferred, or discharged within 4 hours of their arrival, 9.87 percentage points less than in winter 2017/18. Despite NHS England’s pledge to support greater use of Type 3 and 4 UTCs, the footfall recorded over winter did not reflect success in these endeavours.

This winter saw the highest levels of demand and population need across the country, with many national metrics seeing the worst performance on record. Capacity in Type 3 departments was no exception as 4 hour performance declined, raising questions about the role and suitability of UTCs in increasing slack in the UEC system.

POINT 6: Improving in-hospital flow and discharge (system wide) and POINT 8: IPC

The 10-Point Plan highlighted that NHS England would support flow through EDs and work to reduce 12-hour delays. Point 8 relating to IPC measures asserted there should be an expectation of no corridor care. Hospital flow describes the movement of patients through the emergency care system.[5] When EDs cannot transfer patients to a bed or a ward as soon as clinically appropriate, they will become crowded.

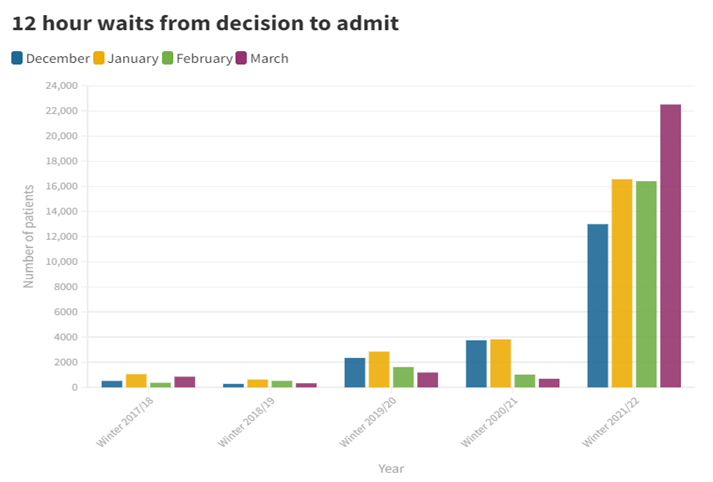

Examining the number of trolley waits, or the numbers of patients who wait from the decision made to admit them, provides us with a good understanding of the extend of crowding and corridor care in our EDs. This winter, NHS England data showed that the number of patients waiting 12 hours from a decision to admit in accident and emergency departments reached a new high. High levels of bed occupancy caused by several factors, including staff shortages and the reduced availability of social care, has resulted in ward beds taking longer to become available to accident and emergency patients. In March, NHS England reported the largest monthly increase on record for the number of 12-hour waits, with an increase of more than 6,000 from the 16,404 recorded in February. The total number of twelve hour waits from decision to admit between December and March increased by 638% over the past year, and by 3783% since winter 2018/19. Furthermore, the number of patients that experienced waits of more than four hours from the decision to admit them onto a ward before being provided with a bed has also increased 68% over the past year.

These severe delays mean that more hospital patients are provided with care in corridors, which is believed to compromise patient safety, privacy and increase levels of distress amongst patients. This issue requires actions to reduce the number of patients staying in hospital beds for extended periods, in order to free up beds, improve flow and avoid corridor care under any circumstances.

High levels of bed occupancy in hospitals contribute to ED crowding and are an important indication that the NHS is under pressure. Maintaining bed occupancy rates of 85% ensures that there’s additional capacity in the system to meet surges in demand and to enable patients to receive the care they need in a timely manner. This winter, average bed occupancy stood at 91.9%, well above the 85% recommendation and 6% higher than the year before.

This winter also saw the highest numbers of long stay patients in hospital for 7 days, 14 days and 21 days or more since winter 2017/18. The GIRFT Emergency Medicine report highlighted where a trust has a high proportion of patients with a length of stay over six days, there is likely to be medical or social delays, which result in increased bed occupancy rates.[6] This illustrates the importance of a fully functioning social care system. While medically fit to leave, patients may need help to recover in the form of a social care package, which may not be immediately available.

POINT 10: Ensuring a sustainable UEC workforce

The 10-point plan acknowledges that ensuring a sustainable Urgent and Emergency Care workforce is a priority. Within the document there is a commitment to work with the Royal Colleges to guarantee there is an improved pipeline for the future by having a long-term plan for workforce across the UEC pathway. RCEM have not been engaged with regarding this, despite repeated calls for the expansion of emergency medicine training places and additional funded consultant posts. In 2021, an average of 15% of total consultant pay was spent on locums, with some Trusts spending upwards of 50%, exemplifying how having understaffed departments drives inefficient spending.

In the short term, the plan spoke of developing new models of care, including, but not limited to, increasing utility of Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC) with the ambition to reduce admissions and ease pressures on existing staff. RCEM’s Snap Survey, taken during the first week of November 2021 revealed that, out of the 70 Trusts that responded, only 10% had wide ranging SDEC in place for 12 hours a day, seven days a week. 81% of Trusts that responded had limited or no effective SDEC in their department, while the remaining 9% of Trusts had wide ranging SDEC, but either for less than 12 hours a day or just on weekdays. These findings show that in the middle of winter, a large number of Trusts were still significantly lacking in SDEC availability.

Conclusion

The UEC 10 Point Action Plan set out steps to recover UEC services over the immediate and medium term. As this briefing demonstrates the NHS endured one of the worst winters in its history; as such, the 10 Point Action Plan failed in its aims to mitigate against current pressures and improve performance in all settings. The plan itself acknowledged that full recovery of the UEC pathway “will take time and require actions beyond this plan”. Despite this, the Government has recently indicated that the 10-Point Plan is the recovery plan for the UEC system. [7]

NHS England plans to publish a UEC strategy this Autumn. To be successful, this must be developed with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The Chief Executive of NHS England recently acknowledged the importance of social care capacity plays in supporting patient flow through hospitals. DHSC must outline steps taken to ensure the social care system is adequately equipped ahead of next winter.

The joint UEC recovery strategy must also contain timelines, targets, and be backed up with additional resource. There must be joint accountability for the strategy, which should outline steps to increase staffed bed capacity by an additional 4,500 beds, a plan to retain and increase the social care workforce and emergency medicine clinicians.

[1] https://rcem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Retain_Recruit_Recover.pdf

[2] https://rcem.ac.uk/summer-to-recover/#:~:text=Our%20Summer%20to%20Recover%20campaign,winter%20elective%20surgery%20was%20compromised.

[3] https://rcem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Whats_Behind_The_Increase_In_Demand_In_EDs.pdf

[4] https://rcem.ac.uk/rcem-welcomes-nhs-englands-urgent-and-emergency-care-recovery-10-point-action-plan/

[5] https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/ImprovingPatientFlow_fullversion.pdf

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2022/feb/17/covid-news-live-hong-kong-battles-surge-in-cases-canada-warns-truck-drivers-over-blockade