Many of you will have heard me say we are the safety net of the patient but cannot be the safety net of the system. There has been general agreement with this sentiment but what does it mean in the current environment peri-pandemic? How much of a safety net are we and where and how was the system failing such that we do clinical (and non-clinical) care that should be managed elsewhere? We are all aware of patients having difficulty accessing the care that they need but let us look at some outcomes. I think this will help us consider how we can actively help to reduce inequalities and at the very least make sure that we are not making them worse as we move forward with rethinking urgent and emergency care. A major aim of setting up the National Health Service was to deliver universal healthcare and avoid people being financially crippled by medical bills. This has been successful. We do not generate the awful stories of medical charges causing bankruptcy or patients choosing between medication or food, but we know that there are marked health inequalities in the UK so universal access free at the point of delivery is not enough to deliver equal and good health outcomes for all. We all know that there are many other factors affecting health including poverty, housing, income, and education which all play a major part in the health of the population. These are known as the social determinants of health. Equally important is a proactive public health programme particularly focussed on the early years of a child’s life. We are all aware of how public health has been underfunded over many years. ‘The Marmot review 10 years on’ describes in shocking detail how all social and economic inequalities have widened in the last decade and these have led to a widening of health inequalities, a decrease in life expectancy and an increase in the amount of life spent in poor health for the most deprived. Life expectancy at birth for males living in the most deprived areas of England was 73.9 compared with 83.4 in the least deprived areas; (females 78.7 v 86.3) in 2016-18. [1] Even more worrying is the finding that in 2015-17 women in the most deprived decile spent 34 % of their life in ill health compared with 18% for the least deprived (men – 30% v 15%). Eliminating this inequity must be a priority for any just health and social care system.

‘The pandemic has shone a brighter light on health inequalities’. This is the careful phrase in the latest NHSE planning guidance[2]. What is noteworthy is the use of the word ‘brighter’, acknowledging the inescapable fact that light has been shown on this issue before but that the pandemic has demonstrated brutally the truth of the previous reports such as Marmot. There are five ‘inequalities’ priority areas for 2021/22:

- restore NHS services inclusively.

- Mitigate against digital exclusion.

- Ensure data sets are complete and timely.

- Accelerate preventative programmes that proactively engage those at greatest risk of poor health outcomes.

- Strengthen leadership and at accountability -providers should have an executive board lead for tackling health inequalities.

Scotland is declared the right to health a fundamental human right[3]. The right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. And services should be: Accessible, Available, Appropriate and of High Quality. This is called the triple AAAQ Framework. Wales published reports on the 18th of March 2021 called ‘Placing Health Equity at the heart of Coronavirus Recovery for building a sustainable future for Wales’[4]. This is a joint report between the WHO, the Welsh government, and Public Health Wales with the stated commitment to make Wales a ‘champion’ country tackling health inequalities. The report highlights the disproportionate impact that Covid-19 has had in different ways on, children, young people, women, key workers, and ethnic minorities. Northern Ireland has published a report documenting Covid related health and equalities in October 2020[5].

So, there is a clear intention which we must see translated into action.

So where does all this fit into our bit of healthcare? Emergency medicine staff are always proud of the fact that emergency care is completely free at the point of delivery. We enjoy informing a bewildered tourist who is reaching for their credit card that they do not need to pay for the care that they received. We have resisted attempts to make us check paperwork for patients attending emergency departments to see if they are eligible for NHS care. And so surely our service is truly giving equal access and so equal care to anyone who presents? The problem is that at the same time we have been in crisis and only too aware that our services are struggling to deliver the quality and safety of care we should. And so, the push to focus on what we are really trained to do – Emergency medical care- and push back on the need to prop up a system that is seemingly unable to deliver the healthcare needs of our local population But could we make inequalities worse doing this? What do we know about those who use our services currently?

Work by The Centre for Health Economics published in 2016 showed the people living in the most deprived fifth of neighbourhoods in England suffer nearly two and a half times as many preventable emergency hospitalisations as people living in the least deprived fifth, allowing for age and sex[6].

The GIRFT reviews have highlighted that in 2019/20, there were more than twice as many ED attendances for the 10% of the population who live in the most deprived areas compared with the 10% who live in the least deprived areas.

GIRFT-EM records a deprivation metric for the populations served by each ED. This is the percentage of patients attending the ED who live in the most deprived quintile of households nationally. There is enormous variation between EDs.

Table: Proportion of ED patients from the most deprived quintile of English households

| Mean | Median | Lower quartile | Upper quartile | Range |

| 27% | 24% | 11% | 37% | 1% to 68% |

Data source: GIRFT-EM, 2021

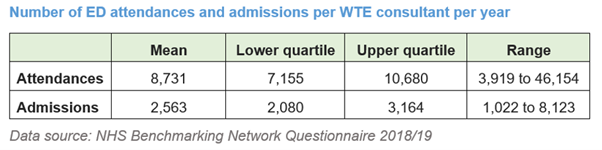

Therefore, demand is importantly determined by the deprivation of the local population but resourcing for urgent and emergency care does not follow health need. The range of WTE consultants is only a proxy measure of resources but the range proves that this is ‘unwarranted variation’.

Many of our least well-resourced departments are in areas of most deprivation. It is hard to justify this level of variation for a service we view are core to the NHS. This is something we as a specialty advocating for adequate resources will need to face up to. New medical schools have been set up in coastal areas in the knowledge that people often end up working in the area they train in. Do we in EM need to think how we make sure that everything we do about workforce truly has population health need is at the heart of decisions made? Will we feel empowered to recognise the need to advocate for better primary care provision and public health in areas with poor health outcomes now rather than provision of acute services to deal with the outcome of the lack of these resources? Can we successfully insist that inpatient teams make sure they have urgent access systems so well know patients can get advice without our involvement and we can spend our time delivering care to the undifferentiated patient?[7] And what can we do to both prevent inequalities widening and may be improve things?

All the reports currently coming out recognising health inequality mention digital exclusion. The pandemic has pushed forward the use of technologies to get patients advice without needing to have a face-to-face consultation. While this works for many it is obvious that some will be left behind. This is where priority 2 of NHSE plans becomes important – how do we mitigate for digital exclusion in the NHS 111 First or NHS 24 system? Patients may not have access to the right sort of telephone, not have English as a first language, have hearing or speech disabilities but all these patients need a safety net to get care when they are in need and frightened. It is therefore important that we are aware of the barriers and are as accommodating to the patient who has problems navigating the system as the educated determined better off patient/ patient’s family who are determined to get a consultation and have the knowledge and resources to be demanding. We all need to be very aware of acting as our most vulnerable patients advocates in a health system that assumes it is accessible and equitable but often is not experienced like that by the patients with significant need.

What else can we do? The Kings Fund report ‘The NHS’s role in tackling poverty[8]’ exhorts us to prioritise Awareness, Action and Advocacy. (The Kings Fund 2021) First we can be talk to our teams and raise awareness of the reality of health inequality in a universal health system build on a desire for equity. We can take action to make sure that new pathways are inclusive- returning the next day for an investigation or treatment may be extremely hard for a woman with carer responsibilities, no transport and a zero-hour employment contract. We can ask for the data from the 111 type schemes to make sure some groups are not excluded. Action can also mean accepting that we can be proactive to public health in Emergency departments and do alcohol and smoking interventions, ask about domestic violence, consider people trafficking, do HIV and Hep C blood tests, vaccinate the homeless and connect them with services, spot lonely elderly patients with multiple co morbidities who need referral, help patients register with GPs. It also means being aware of our own bias and understanding the data. The MBRACE investigation into maternal mortality makes scary reading. We need to know that pregnant women who are recent migrants, asylum seekers or refugees, or who have difficulty reading or speaking English, may not make full use of antenatal care services but may come to the Emergency department. We need to know that Black and Asian women are at a higher risk of dying in pregnancy. (MBRACE 2020). We need to teach about and use resources like Skin Deep (A DFTB project) which aims to improve education and recognition of conditions in all skin tones. We need to respect the need to have language service appropriate to our area and accept that reasonable adjustments may add time to care. We know our teams may not look like the population we serve and have little knowledge of what may be important to that population. Friends and Family tests tell us very little about our actual patient experience.

Advocacy means highlighting to policy makers how Emergency departments are often the safety net and ask them to accept that this function needs resourcing but also that others might provide a better service which lead to long term health benefits – we can treat stabbed teenagers and we can refer them to youth violence programmes but how much better to have given them some sense of purpose earlier on and not need us at all for this.

The final priority of NHSE inequalities plan is about showing leadership. I think EM clinicians are in a special position here. We see the full spectrum of patients that many other professionals only see sub sections of. We see the effects of poverty and we see the effects of diminished public health efforts in the last decade. We have seen how underprepared we were to deal with a pandemic and that the measures needed hit those least able to comply with those measures. We need to think regionally about how our population is served best by what resources and facilities there are. We have seen amongst our own teams the variation in trust in healthcare messages and the risk that can pose to individuals health. So, we need to work out how to be a better safety net and better advocates for the health services our local populations need.

With thanks to Ling Harrison and Chris Moulton but all errors my own.

by Dr Katherine Henderson, President of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, FRCP FRCEM

*this is an article taken from the Emergency Medicine Journal – Supplement – May 2021 Edition

[1] https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

[2] https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/B0468-nhs-operational-planning-and-contracting-guidance.pdf

[3] http://www.healthscotland.scot/health-inequalities/the-right-to-health/overview-of-the-right-to-health

[4] https://phw.nhs.wales/news/placing-health-equity-at-the-heart-of-coronavirus-recovery-for-building-a-sustainable-future-for-wales/

[5] https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/coronavirus-related-health-inequalities-december-2020

[7] https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/Policy/Improving_medical_pathways_for_acute_care.pdf

[8] https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-role-tackling-poverty